Written and edited by: Eszter Ruttkay-Miklián

Éva Schmidt: Journal, 1970

Introduction

Éva Schmidt spent the 1969/70 and 1970/71 academic years in Leningrad as an exchange student, and in addition to her university studies, she attended classes held for native Khanty and Mansi students at the Institute of the People of the North of the Herzen Pedagogical University. This is where she formed her first personal relationships. She became lifelong friends with one of the Khanty students, Taisija Stepanovna Seburova (02. 23. 1949 – 10. 19. 2020), and they traveled together to her native village, Tugijany for the winter holidays at the end of January 1970.

Éva Schmidt’s first expedition was not just an extraordinary adventure for her personally: it was also an exceptional opportunity in scientific history, given that no foreign researcher had been able to conduct field research among the Ob’-Ugrians since the existence of the Soviet Union. The only exception to this had been the journey that Wolfgang Steinitz took in 1935.

In spite of this being such a unique event, the sources available to us are quite scarce. People who knew Éva Schmidt might have heard her drop a few words about the adventurous trip: ’Wearing just a trench coat’, ’in -40 degrees’, ’accidentally’, ’with the Komsomol’s permission’; but not much more than this. This is why the journal that was recovered during the organization of the legacy, as well as the four rolls of negatives with some 120 photographs that were made during this time are of key importance.

After obtaining the necessary permits and documents –the reconstruction of which is impossible today – Taisija Seburova and Éva Schmidt traveled for the winter holidays together with many of their fellow students. The journal reveals to us the following travel itinerary: they set off from Leningrad to Tjumen’ on January 23, 1970, and flew on to Berёzovo the next day, then further on to Polnovat on January 26. From there they traveled to Tugijany by horse sleigh. They spent a week in the village, from where they traveled back together to Berёzovo via Polnovat. From here, Éva Schmidt traveled alone to Khanty-Mansijsk, while Taisija Stepanovna returned to Leningrad. Éva Schmidt flew back to Leningrad from Khanty-Mansijsk through Sverdlovsk. Another fact we learned from the journal is that Éva Schmidt’s tape recorder broke, so she did not make audio recordings on this journey. Her collection comprises the set of photographs – in addition to the experiences.

In Tugijany

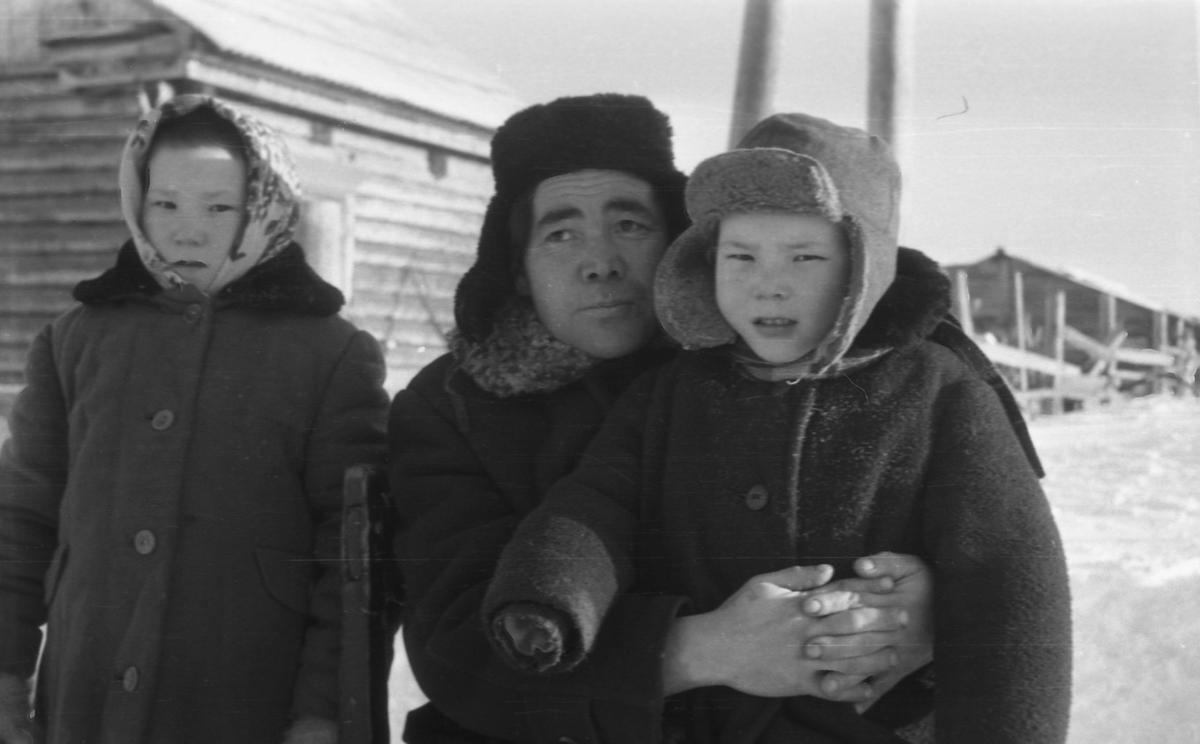

The winter of 1970 brought record cold to Western Siberia. According to the journal’s testimony, even the locals were struggling with the frost, so Éva Schmidt could gain a strong impression of the northern circumstances. She was given the opportunity of an in-person encounter with this world, about which she had plenty of theoretical knowledge, having read the literature, studied the language, corresponded with Khanty people, and read the Khanty newspaper. However, transferring in -45 degrees from a small aircraft to a horse sleigh, being dressed in a traditional fur coat and boots, being offered bear meat as a guest only after the spirits had been fed, hearing his dinner companions unexpectedly break into song for their own amusement, and then seeing them perform bear ceremony dances to her, are experiences she could only have personally in the field. She saw the daily life and material world of a small village by the Ob’. In the photos we find that the traditional object culture and and the ’Russian’ world of shops coexist, however, the presence of traditional objects was a noteworthy fact: from her journal we learn which house the sewing kit in the birch bar box were in, where the baby was lying in the birch bark cradle, and in the photos we see the simultaneous use of pieces of traditional attire and store-bought footwear and coats. The bases of the economy in Tugijany were fishing as well as cattle and horse husbandry, which Éva Schmidt had been familiar with in the way they were done in Hungary. This often served as a common basis during conversations and daily activities.

She reports great difficulties with understanding the Khanty language in the beginning. In the case of older Khanty and Mansi speakers, it was sometimes hard for her to even tell whether they were speaking their mother tongue or Russian with Ob’-Ugric intonation and accent. During her studies, she had learned the Middle Ob’ (Šerkaly) dialect spoken further south, so she found switching between this and the dialect spoken in Tugijany very challenging: „…the radio was broadcasting a 15-minute program in sharp Mid-Ob’ dialect, only it was very crackly. Even so, I understood it better than I did the locals...”

The week spent in Tugijany was mostly spent paying visits to the relatives with Taisija Seburova, and in turn they took their part in entertaining guests at home. The village residents also showed keen interest in her person, they interrogated her about family relations, comparing the two ways of life, and she even sang to the Khanty hosts. She got to know the local dialect, folklore, singing style, and met several excellent informants. During her subsequent trips, she collected valuable material from several residents of the settlement. From then on, Tugijany and its culture became the reference point that helped her organize the knowledge gathered in the other areas she subsequently traveled to. Thus, the first expedition was definitive in all respects.

Inclusion: Khanty sister, Khanty mother

A symbolic manifestation of the deep and intimate relationship that was formed with the village of Tugijany and its residents was that Taisija Stepanovna Seburova’s family adopted Éva Schmidt as their daughter. Taisija Stepanovna Seburova played a crucial role in the relationship that Éva Schmidt formed with the Khanty people. Their friendship lasted as long as they lived. Taisija Stepanovna recalls that in the fall of 1969, their teacher in Leningrad, Matrёna Pankratevna Balandina (Vakhruševa) informed them, the Khanty students, that a Hungarian girl would like to correspond in Khanty. They were not very enthusiastic, perhaps it was the connection with a foreigner that scared them. However, Éva Schmidt soon turned up in Leningrad in person, and started to attend classes with them. Taisija remembers being surprised that the new student was not using makeup, and was also less interested in the great museums of Russian culture than in making conversation with them in Khanty, about the Khanty. A result of their deepening friendship was the expedition to Tugijany in 1970, which was followed by Taisija’s trip to Hungary in 1971. Taisija Stepanovna lived in Khanty-Mansijsk and worked in Khanty cultural affairs: she was the editor of the journal Khanty Jasang for a long time, she published several papers by Éva Schmidt from her Khanty collections. She followed the work of the Belojarskij archive, participated at conferences and events. She continued helping Hungarian expeditions after Éva Schmidt’s death.

In Khanty-Mansijsk

Journal

About the manuscript

Éva Schmidt’s journal of the 1970 trip was recovered during the processing of the legacy, however, it was a typewritten copy, and not the original handwritten text. From the layout of the 17 pages of typewritten text we can see that the author left out space for photographs within the text, adjusted to the margins. Though we have Éva Schmidt’s photographs taken at this time, we cannot reconstruct the photos to be inserted. The journal entries cover the span from January 23 to February 1, 1970, and then the events of a few days are summed up and added to the text at a later date. After the 14 numbered pages, in the section marked a, b, c at the end of the typed manuscript, we find a data summary under the title ’Some data about Tugijany’, which already contains the date 1975. This suggests that the typed version was completed at a later time, it might even reflect the experiences from 1980 and 1982. We have no information about who she prepared the account for and with what purpose; the journal entries serving as a source were obviously put down for herself, but she probably had some specific aim with preparing the typed version. Meanwhile, it informs the contemporary reader about the itinerary, the events and circumstances, as well as the 22-year-old Éva Schmidt’s first impressions about the land of the Khanty. As there is no official report of this journey that we know of, this reflexive document written in a personal tone is of key importance, so we are publishing both the copy of the original typewritten text and edited version complete with notes.

In the edited Hungarian text of the journal, we corrected, unmarked, the spelling errors that obviously resulted from the nature of the typewritten text or misspelling, and spelled out the acronyms. On the other hand, we kept the idiosyncratic use of language, and did not unify the transcription of Russian (Khanty) names, so they divert from the transcription standard used elsewhere on the website (e.g. Kalestrat – Kalistrat). Éva Schmidt’s footnotes were incorporated in the text, and footnotes were reserved for the editors’ remarks. Editors: Márta Csepregi – Andrea Kacskovics-Reményi – Eszter Ruttkay-Miklián

Éva Schmidt’s journal of the 1970 expedition

Photos

About the collection

Among Éva Schmidt’s photographs, there are four rolls of 24x36 mm black and white negatives about the 1970 expedition, comprising a total of 124 shots. Paper pictures were also made from the negatives, often in several copies and different sizes. The quality of the pictures varies, but despite this fact, we are publishing nearly all the photos; the only pieces we did not publish were ones where, for example, there were several shots in the same position, and we found it sufficient to present only the best shot. A number of the paper photos were well known among both the Khanty people and the researchers in Hungary, but the full collection has not been published so far. She took mostly outdoor pictures, obviously due to the light conditions. The portraits and group photos are primarily staged situations. In addition to these, Éva Schmidt took panoramic photos of the village, as well as her forever favorite subject, the animals.

About the processing

Currently both the negatives and the paper copies are in the Éva Schmidt Archive. The pictures were organized, digitized and digitally post-edited by Andrea Szabó at the Data Archives of the Institute of Ethnology of the HUN-REN Research Centre for the Humanities. She smoothed out the negatives that had been kept in rolls for 50 years, digitized them and placed them in storage adequately. She identified the negatives of the paper copies. She also digitized the paper copies where needed, primarily in cases where they have data or inscription on the back side.

Arranging the photos in the four rolls of film from 1970 in chronological order does not seem to be a difficult task, and yet it has proved to be impossible. Some moments can be identified unanimously, for example the last picture in Tugijany before Éva Schmidt’s departure, where she herself is dressed in warm clothes in the group photo, ready for the trip. However, in one of the rolls, between the shots of moments of life in Tugijany, we find a series of pictures taken in Polnovat. By the logic of the journey’s itinerary, these could only be taken on the way there or back, and we could not figure out how they got mixed with the photos taken elsewhere. In her journal, Éva Schmidt repeatedly mentions that she took photos thanks to the good weather or that, at other times, she would have wanted to take pictures, but circumstances did not allow. Yet we could only link the photos to the journal in some exceptional cases.

Several options presented themselves for adding data to the pictures. On one hand, there are bits of information on the back sides of the paper pictures, the majority of which originates from Éva Schmidt. These usually indicate the person, place and time, or briefly describe an event or object.

We are publishing the information from various sources along with the pictures. We find it important to make the sources of these metadata traceable, so we are presenting them separately. The data were organized, translated and edited by Levente Máthé, Eszter Ruttkay-Miklián and Andrea Szabó.